“It was the best of lines, it was the worst of lines, it was the age of drifting, it was the age of gear ratios, it was the epoch of arcade racers, it was the epoch of racing simulators, it was the season of vibrancy, it was the season of realism, it was the spring of light grooves, it was the winter of dark trance, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us — in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest disc jockeys insisted on its use being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

– Charles Dickens, probably, if he had lived another 130 years and played Ridge Racer

IGNITION

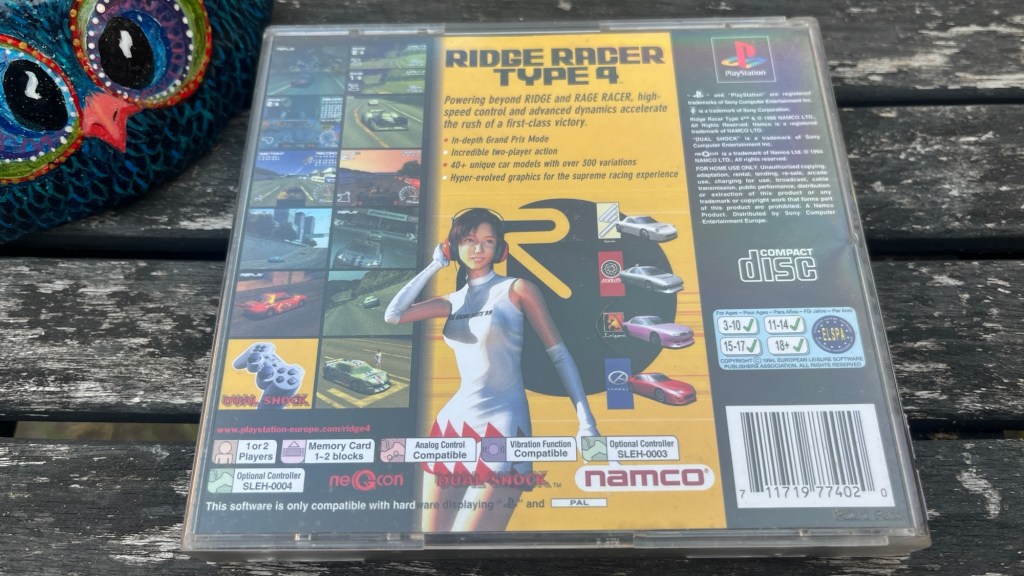

I’ll admit I was spoiled on Namco’s Ridge Racer series with R4: Ridge Racer Type 4 being my introduction to it. It must’ve been early 2000. Anticipating the PS2’s launch and the Dreamcast’s parade of late-Y2K bangers, I figured R4 would at least help bide my time. I was only vaguely familiar with the Ridge Racer franchise but it seemingly embraced its arcade racing lineage, and in a post-Gran Turismo world no less. In the dawning age of racing simulators, I respected its defiance.

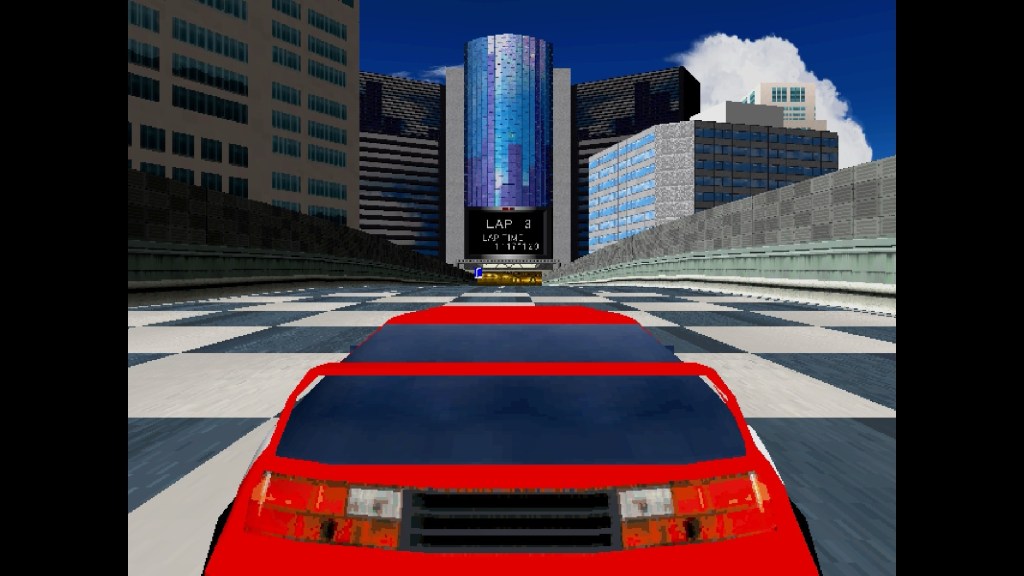

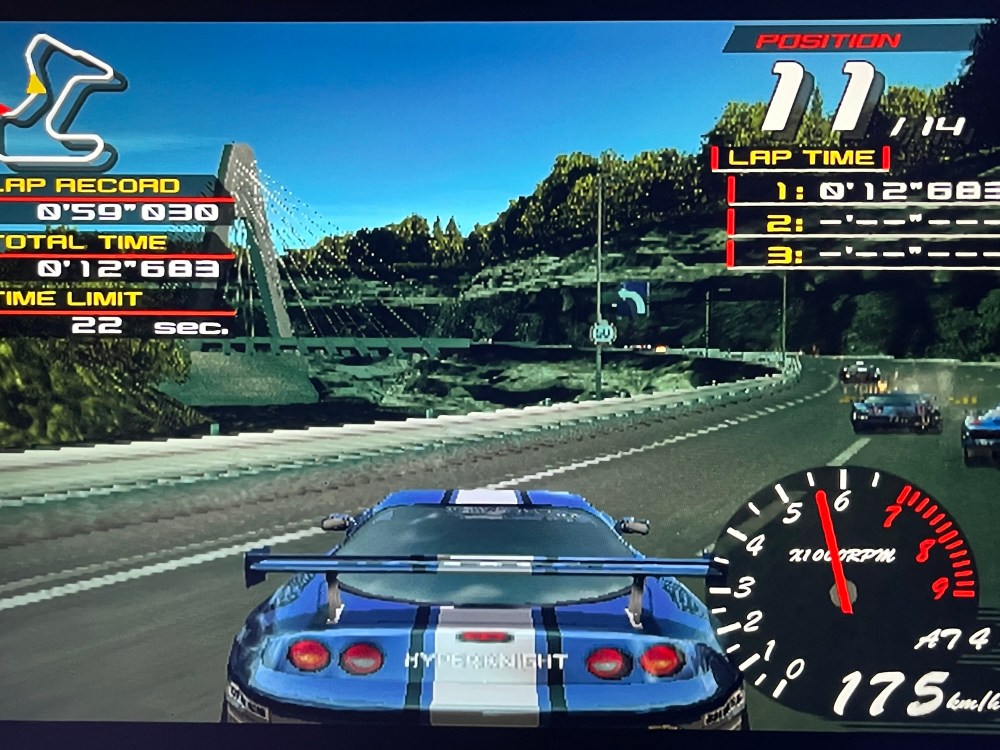

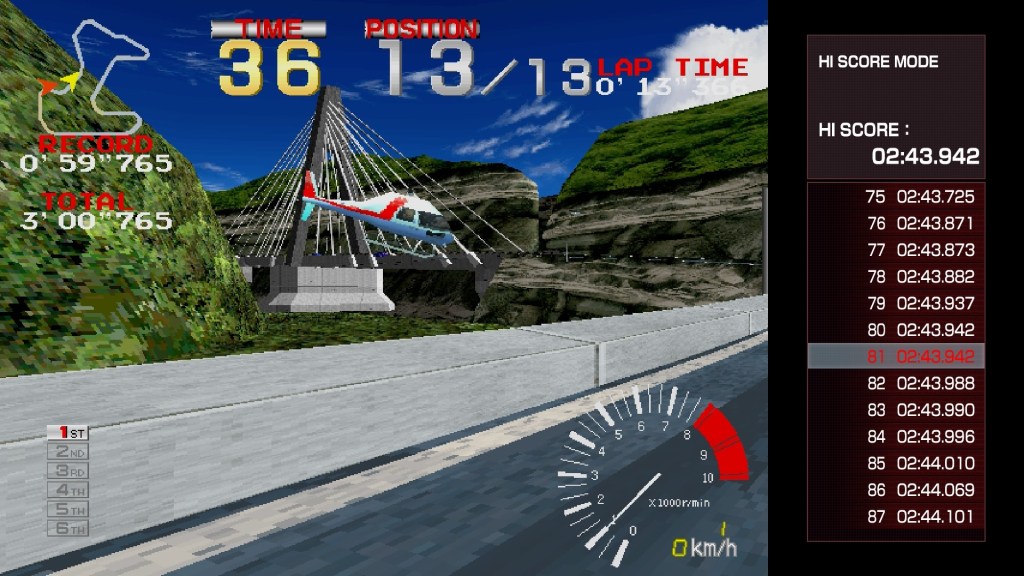

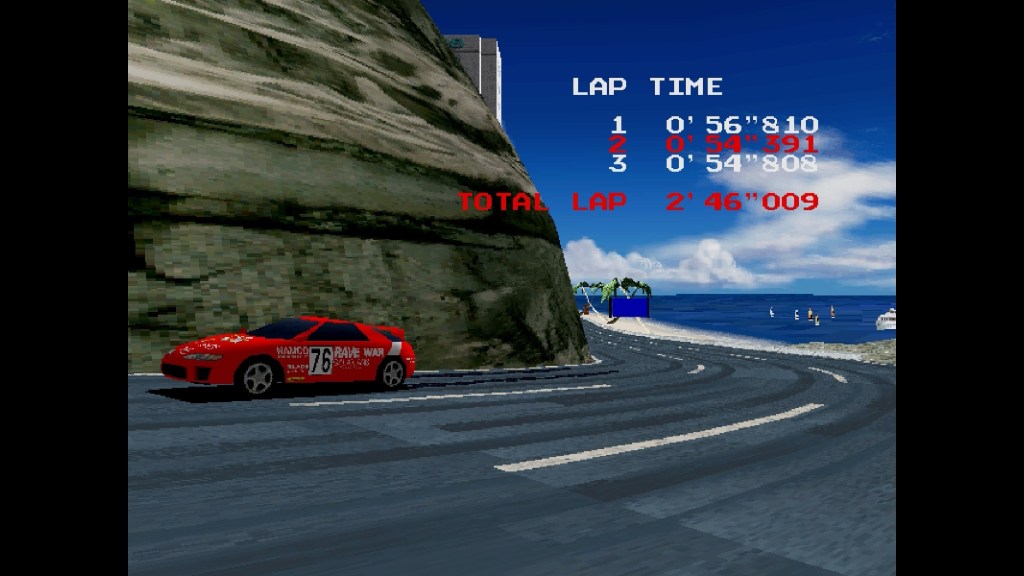

Edge of the Earth, the New York race course | R4

Today — just as it did then — R4 more than captivates. From the opening moments of its impractically stylish intro — where virtual spokeswoman Reiko Nagase casually strolls down a highway, breaks a high heel, and then hitches a ride in a race car — I’ve yet to escape R4’s resonance. The game’s attitude, aesthetic, and soundscape exudes a sense of style as substance. R4 envelops me in its multi-sensory barrage like the most kinetic cockpit arcade racers, immersive VR experiences, or any random Tetsuya Mizuguchi game. That it also happens to be a joy to play is one hell of a bonus.

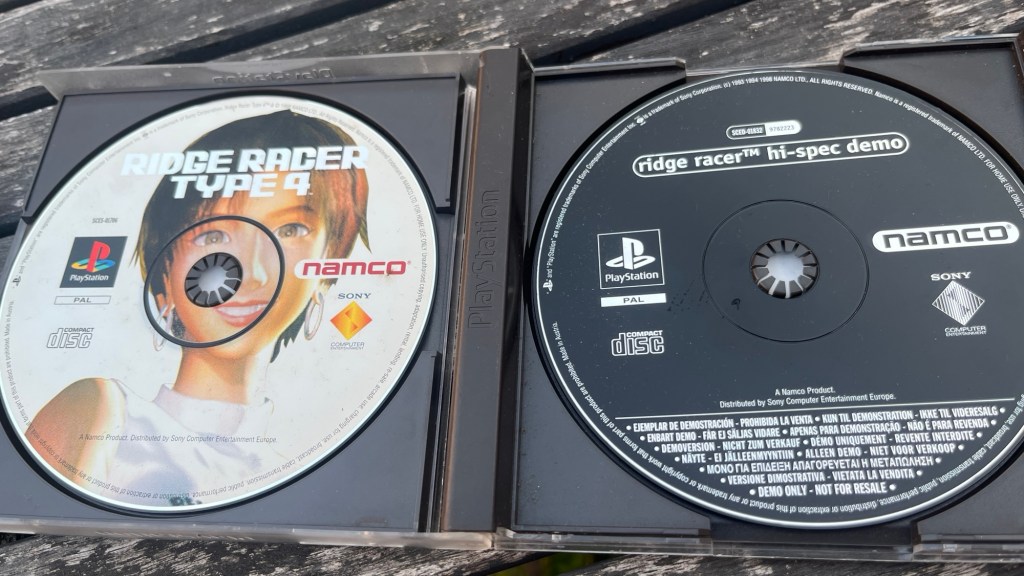

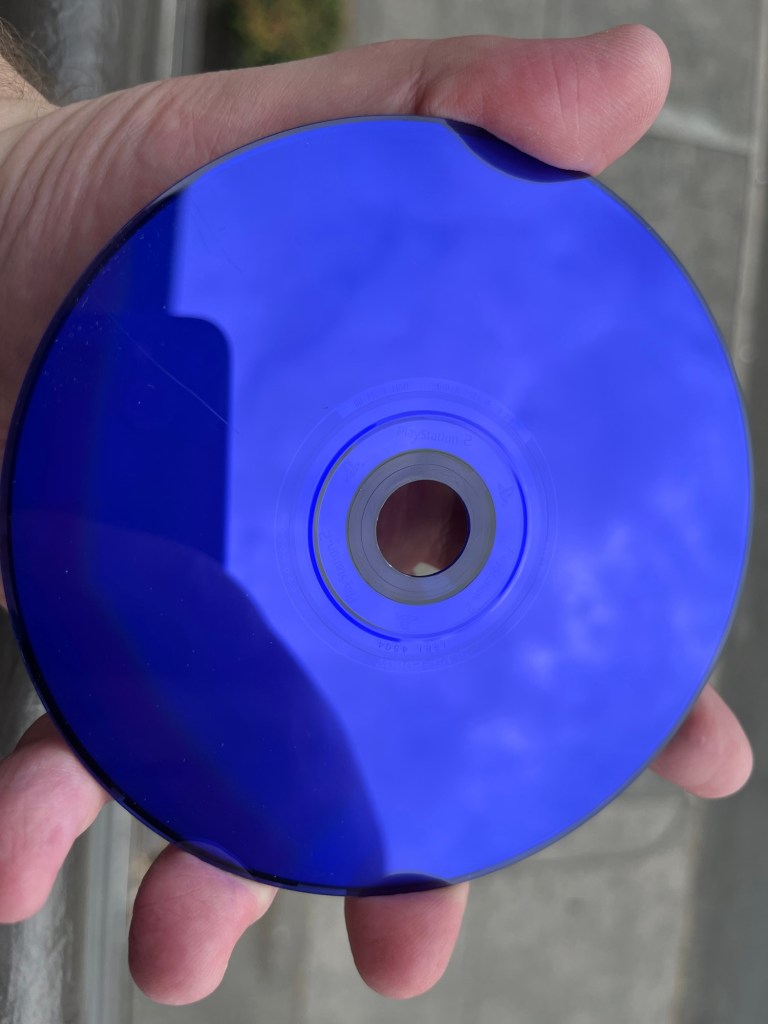

It also came with a demo disc, which I eventually got around to playing.

It was a Namco sampler compilation featuring a readaptation of the original PlayStation Ridge Racer from 1994/1995, which itself was an adaptation of the original 1993 arcade racer. However, this version was revamped and truncated for a smooth, 60 frames-per-second experience. It would be my first foray into the series’ (real racing) roots.

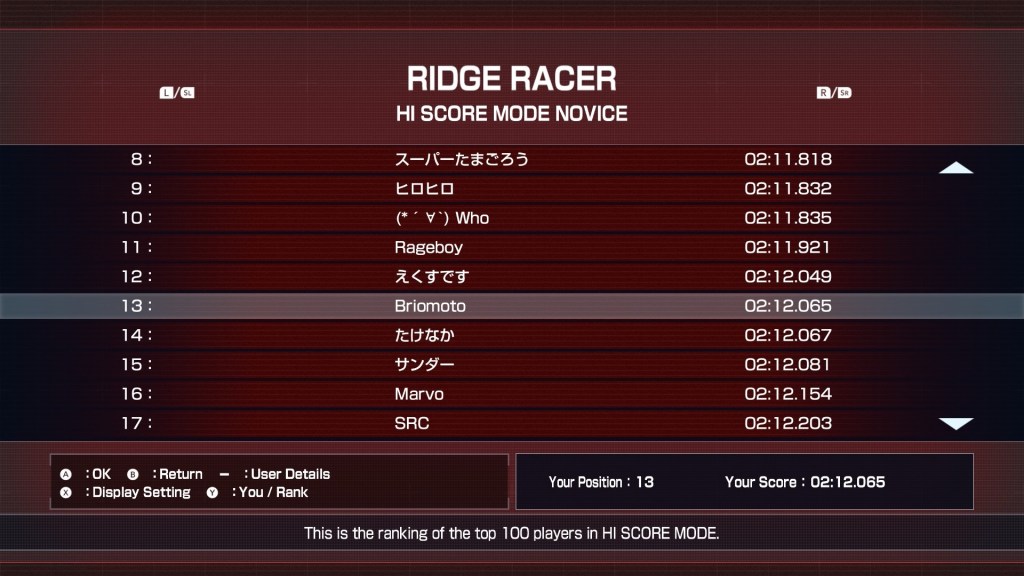

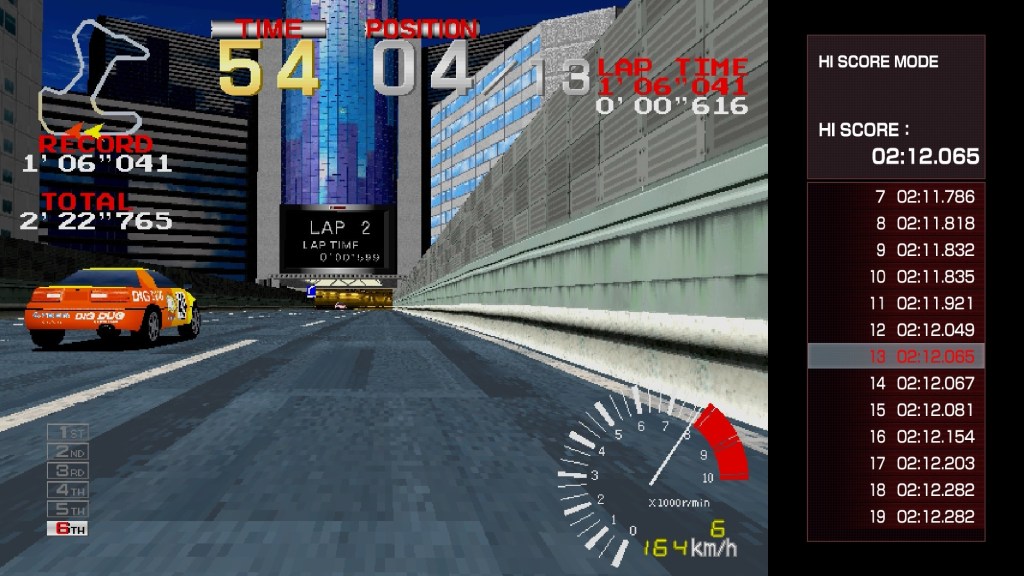

But now the arcade original has been released on modern consoles and I’ve been playing it all week.

MOVE ME

In its setting of Ridge City, a single race course treads a careful line between natural scenery and built space. Its starting line is nestled in a bustling downtown district. The initial straightaway ushers racers into the gullet of a glass skyscraper, its tunnel a portal beyond the city. They emerge in a mountain valley pass, crest the titular ridge, coast along a sandy beach and restaurant-lined promenade, and circle an expressway* back to the city proper.

* The expressway is either brief or meandering depending on whether you race the standard or extended variation of the course.

As a backdrop for the racing action, Ridge City leaves little to explore — spatially — beyond its rudimentary trackside features. Yet in its meager polygons, saccharine hues, and crude textures, it depicts a place I can imagine myself inhabiting. Each area of the city feels memorable and personal, driven to life by landmarks and daydreams.

In the morning, I can imagine waking to the ocean views of its resort hotel. I’d walk the beach and take in the ocean air over breakfast and coffee on the promenade. I’d ascend the ridge for a mid-day hike (preferably not in high heels). Then I’d climb to the lighthouse for lunch with a view. At dusk I’d hit the town, bouncing between skyscraper rooftop bars while watching racers floor it down the final stretch below.

In its dearth of definition, the original Ridge City invites my imagination to — not just fill in the gaps — but to coauthor its bustling world. And through our collaboration, my immersion solidifies.

I continue to find the original Ridge Racer’s setting every bit as inviting as its legendary peers, Daytona USA and Sega Rally Championship. Standing amid their pantheon, Ridge City shatters any notion that Sega had a monopoly on blue skies vibes.

EAT ‘EM UP

Drifting into the new millennium, the PlayStation 2 cast its shadow over gaming culture and beyond. Its dominance was preordained. The PS2 commanded a tsunami of brand clout and DVD format stewardship. It would be next generation’s de facto kingmaker. For the faithful customers worthy of its benevolence, Sony just needed us to know that we too could wield its awesome power. Want realistic visuals? Easy. Want to be the coolest kid in your neighborhood? Done. Want to operate ballistic missile guidance systems? Theoretically possible.

Power to the fuckin’ players, man.

Practically speaking, the PS2’s sheer technical strides promised such incredible fidelity, we’d needn’t strain to imagine ourselves in its virtual spaces. As if that wasn’t the whole fun of it.

Meanwhile, Gran Turismo was unstoppable. Its first two entries upended the traditional racer paradigm with heaps upon gobs of almighty content. Hundreds of licensed vehicles. Dozens of race courses. Limitless upgrade and customization options. Dynamic, TV style replays. A commitment to realism such that mastering its virtual facsimile could beget a professional racing career in real life. Gran Turismo’s tour de brute force rendered anemic any racing games that failed to evolve under its influence.

Between mainline Gran Turismos, developer Polyphony would later release trimmed-down concept demo discs that were still larger than most full games in the genre.

The Gran Turismification of the racing genre was in full swing. At a minimum, Gran Turismo decreed that the next generation of racing games ought to be feature-packed and plausibly mistakable for real footage. Those with toy-like visuals and a small handful of cars and courses would no longer cut it; however fun and timeless they felt to play would be immaterial. GT’s success rendered “arcade-style” racers all but stigmatic. It was nothing personal: their value propositions were simply inferior. And if their publishers dared charge the same $40-50 as Polyphony’s robust masterpieces, why shouldn’t the free market shun them as scammers?

Content is king, so they say.

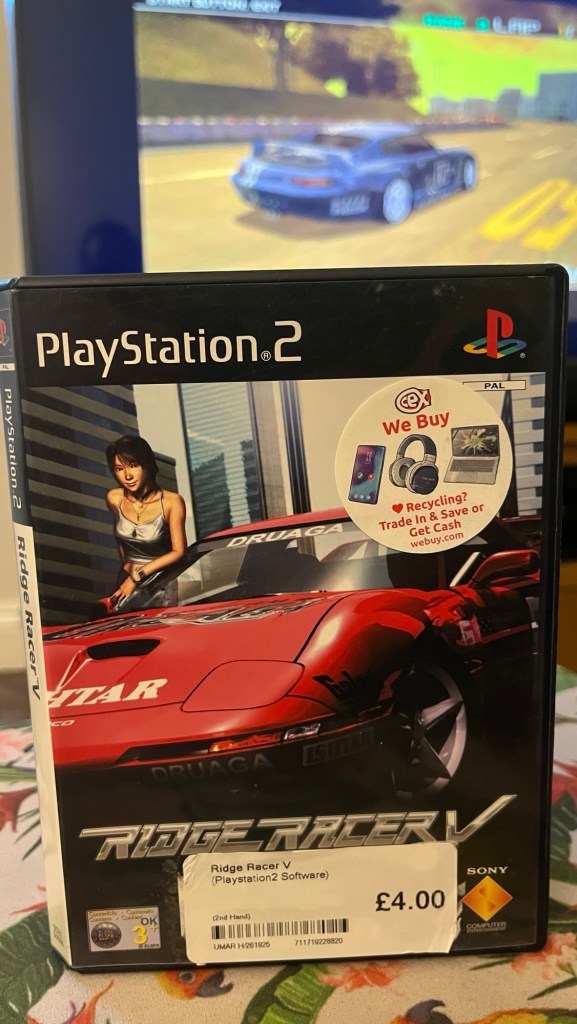

Namco’s next gen entry in the franchise — Ridge Racer V — bowed to the mandates of the PS2. The original Ridge Racer had been the inaugural killer app for the first PlayStation launch. But this time, Ridge Racer V needed the PS2 far more than the PS2 needed it. Sony had plenty of showpiece fodder with or without Namco’s help. And even if SSX, TimeSplitters, Armored Core 2, Dynasty Warriors 2, and the rest of its dozens of launch titles…Kessen…Eternal Ring…And even if…Fantavision…even if they failed to sell the console, a vague gesture towards the looming Gran Turismo 3 (GT2000 at the time) would obliterate all doubt that the PS2 was the next big thing.

Ridge Racer V, by comparison, was lucky to be along for the ride.

Evergrace.

MOVIN’ IN CIRCLES

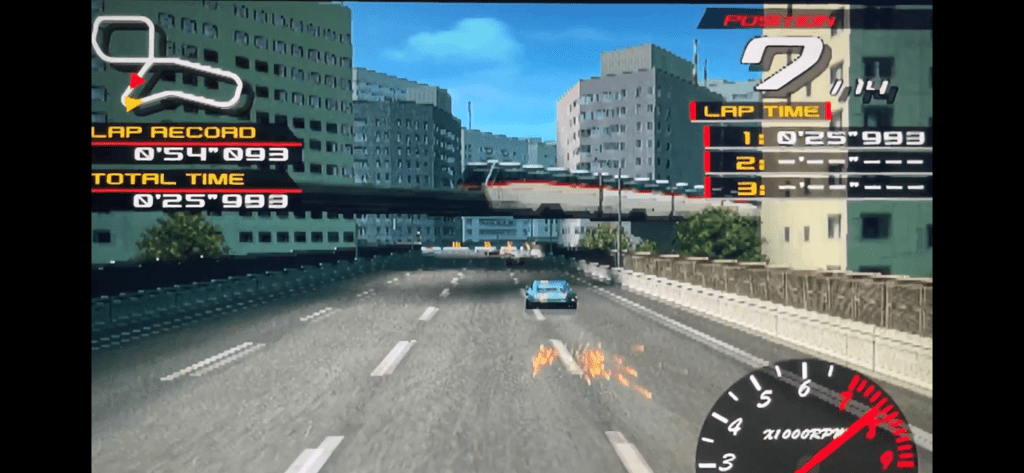

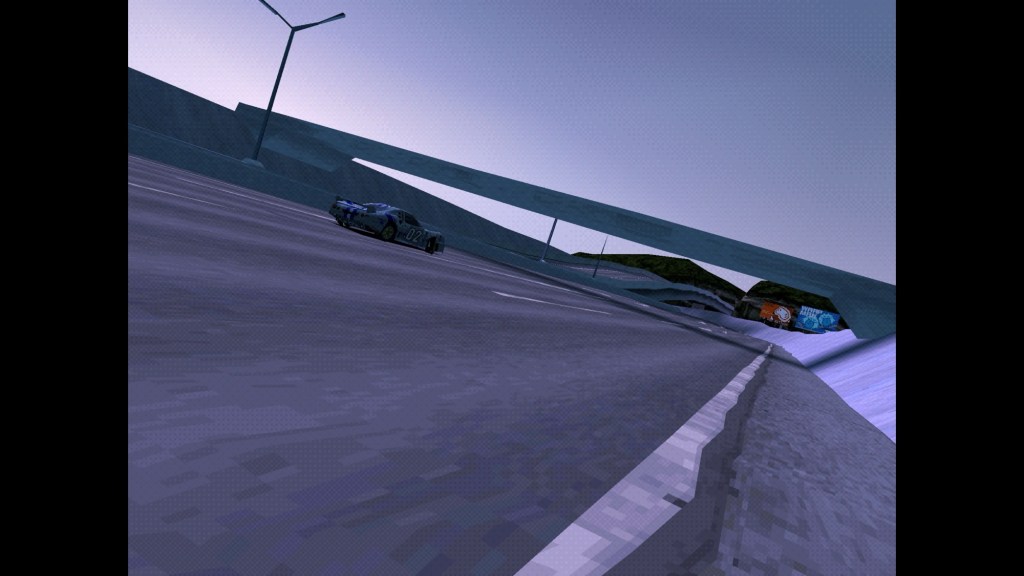

Ridge Racer V returns us to Ridge City, or at least a larger, more grounded reimagining of it. The city’s core layout remains familiar. Many of its landmarks preserved in some form or homage. But the vibes are — if not off — at least a little stagnant.

This Ridge City has grown more expansive in the five years between PlayStations. Its depths and edges unfurl over a half dozen courses in a steady cadence of four-round grands prix. Each track drifts in and out of their interwoven routes but they all revolve around the same nucleus of midtown overpasses and underpasses.

The intertwining courses promised to imbue this Ridge City with a sense of density and multi-dimensionality. I’m a sucker for that concept, in theory, and I like how it was utilized in Rage Racer before it. But in practice, most of RRV’s courses are just slight variations on others. They share too many of the same spaces to feel unique and the few diversions they do make are rarely interesting or memorable. Counterintuitively, the multi-layered course designs simply grant more ways to see how small and stifling Ridge City really is. That probably wasn’t the intended effect.

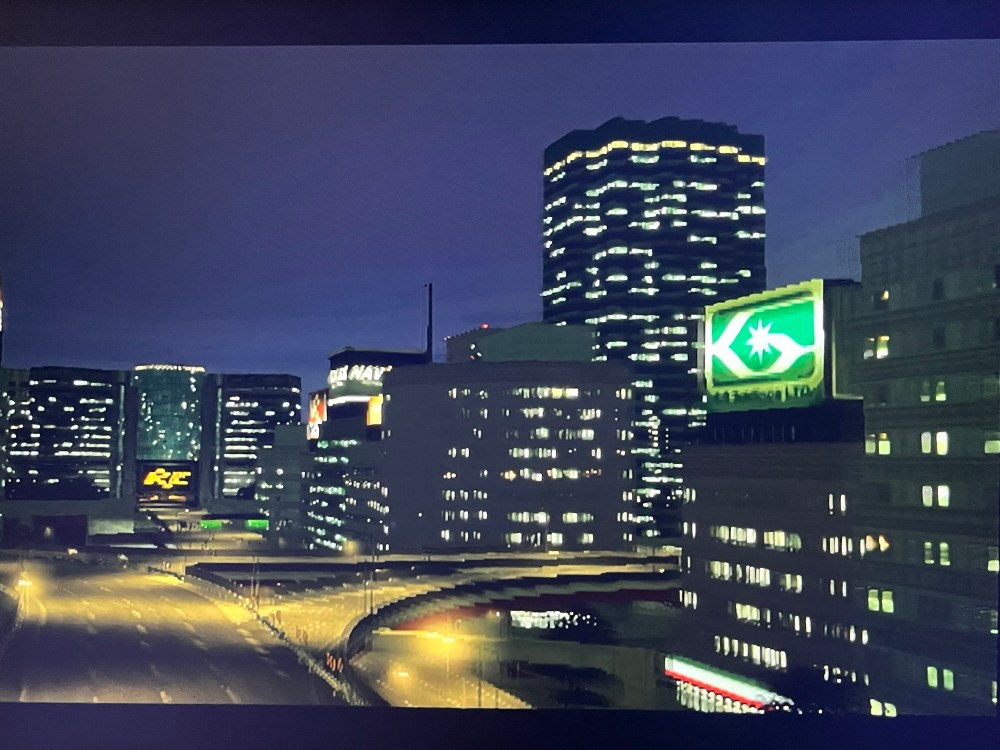

Aesthetically, this Ridge City rejects its vibrant heritage in favor of sensible realism. It feels more subdued. Edgier. Prettier. Sterile. I wouldn’t say it’s soulless but it’s not not soulless, either.

For anyone living in communities reshaped by the overbearance of big tech and other conglomerates, Ridge City’s transformation in RRV may seem distressingly familiar. I’ve been there before. Hell, I lived in that city for over 15 years. The imagination needn’t wander far to infer its ruin.

Ostensibly, it would’ve taken an army of corporations, real estate developers, and contractors to reshape Ridge City into the unrecognizable state it exists in here. But it wasn’t enough just redevelop it. They had to disrupt it. To think they threw all that vulture capital at Ridge City just to make it prettier and shittier.

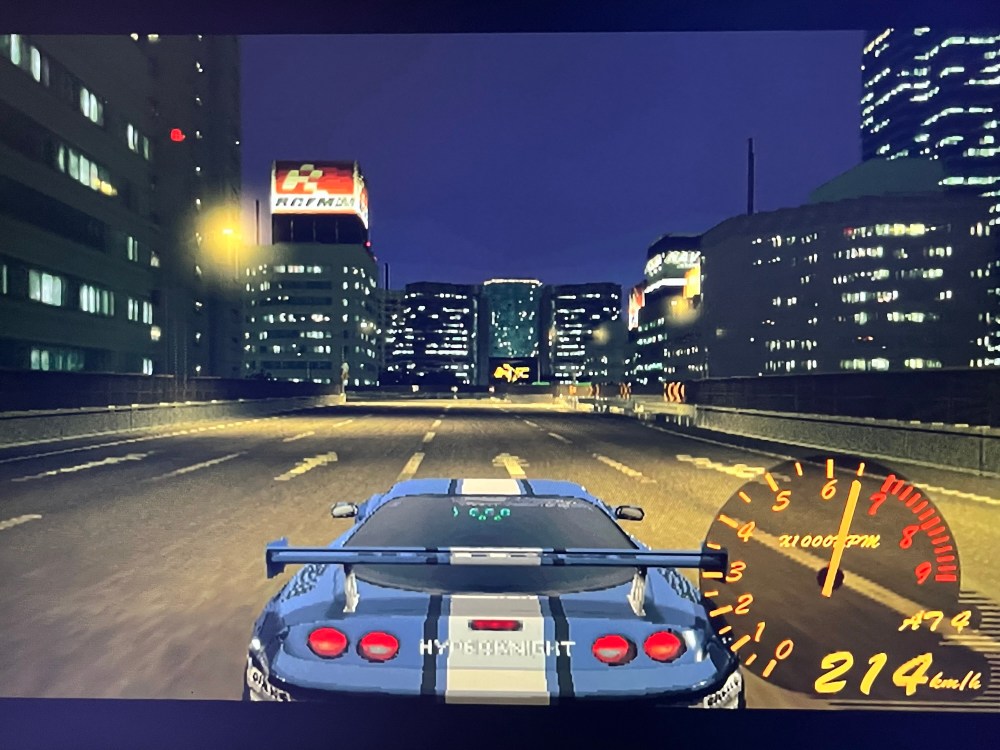

They demolished most of the skyline along with its eclectic architecture and half-moon windows. In their place are clusters of boxy office towers — perhaps inspired by Shinjuku’s medium rises — but sans the neon wayfinding, tonkatsu ramen houses, or any discernible charm of their own. Their nondescript facades sterilize Ridge City’s streetscape. Their office floors radiate into the night. Their branded roof signs are immaculate.

The reconstructed skyline is ornate. Attractive. Superficial. It evokes ambience for ambience’s sake. If this Ridge City is indeed a place people call home, it has abandoned such trivialities as public spaces or culture.

Outside the city center, the natural areas and landmarks have been preserved in a loose sense. The resort hotel, lighthouse, and petrol station have been renovated to look as bland as possible. The promenade’s shops, cafés, and eateries have been razed and replaced with private, fortified villas. Looping, desolate freeways isolate the city outskirts. Only when an odd monorail, truck, or airplane grazes overhead does Ridge City suggest people still traverse its spaces, even if it’s just to pass through them.

Lest our loneliness gnaws at us, the local radio DJ chimes in periodically to remind us that big racing things are happening around the city. His pep talks trip over amusing mispronunciations of words like “ROO-kie” and “CON-gratulations”. He means well, bless him, but we know we’re on our own here. Off the mic, he resumes the blazing trance beats and shrill, distorted riffs that juxtapose the city’s drowsy vibe. We appreciate the thought but — as we circle the void — they provide little COM-fort.

Although RRV’s Ridge City fails to ignite my imagination as a habitable space, I adore cruising its sleek streets. And it really is a gorgeous setting, aliasing be damned. In Namco’s pivot to a more grounded aesthetic, the city appears both striking and serene. At night, its highways bathe in an incandescent glow. The cars sheen and flicker under street lamps and — with their low suspensions — they ignite blooms of sparks at the faintest hint of an incline to scrape against. Meanwhile, the coast is stunning in dusk’s tinge, even if the seaside redevelopment banishes all but the wealthiest holiday goers from taking it in.

THE OBJECTIVE

The years between the first and fifth Ridge Racers marked a period of upheaval as video games scrambled to find their footing in the third dimension and legitimize themselves as a creative, culturally significant force. As game makers sought to chart the future, they pioneered an array of concepts, mechanics, and technologies in hopes of progressing the medium forward in meaningful ways.

Many inventive — if rudimentary — early 3D games like the original Ridge Racer challenge us to interpret their spaces more actively, and place ourselves in worlds they may have struggled to depict in great detail. They empower us — not only to suspend our disbelief — but to apply more of our imaginative selves to the experience. In this way, the original Ridge City remains an unlikely playground for our curiosity.

Meanwhile, the insatiable drive for hyper-detailed realism — spoon fed to the player for convenient, passive consumption — is neither an ends nor means. It’s a detour. It can support a strong, underlying vision with new things to see along the way, but it contributes little lasting impact on its own.

With a quarter century of hindsight, Ridge Racer V may have been my first glimpse at the diminishing returns inherent to the fidelity arms race. RRV committed itself to visual spectacle but made few impacts of its own invention. It stumbled into the next generation under others’ more calculated terms. I imagine a brutal launch development schedule certainly didn’t help. More fundamentally, RRV neglected to interrogate how Ridge Racer could thrive as a unique, next gen experience. It failed to pave a vision unmoored from the trappings of launch day pageantry, Gran Turismification, and its own lineage.

In their dueling visions of Ridge City, the contrasts between Ridge Racer and RRV help illustrate the state of the series over a fascinating period for the genre. The original Ridge Racer’s experience endures — not because it had cutting edge graphics for 1993 — but because it cultivates a distinct personality that unfolds as players discover the minutiae of its curves and idiosyncrasies. It set the pace for how racers would evolve during the genre’s pioneering renaissance. Meanwhile, Ridge Racer V looked stunning — and still plays great — but it retread a well-worn course with few distinct ambitions beyond being filler for a console launch a quarter century ago.

And yet, R4 — because of course this would come back to R4 — occupies a universe of its own. It holds back little in its aspirations for both sensory impact and realism on its own terms. Regardless of how the genre evolved beside it, R4 commits to a vision that rallies its aural, design, and stylistic innovations around a captivating and timeless vibe. It’s an experience that — more than 25 years onward — continues to make players feel cool.

Truly, R4 spoils us still.

POSTSCRIPT

Well, damn. I originally planned to focus on Ridge Racer and Ridge Racer V for this post but the comparisons kept leading me back to why R4 fucking rules. And I never even got around to discussing the soundtrack which is, like, that game’s whole thing.

I also didn’t expect to my critiques of RRV’s setting to be so…much. I wanted to explore why RR1 felt more immersive to me and that led me down a rabbit hole, I guess.

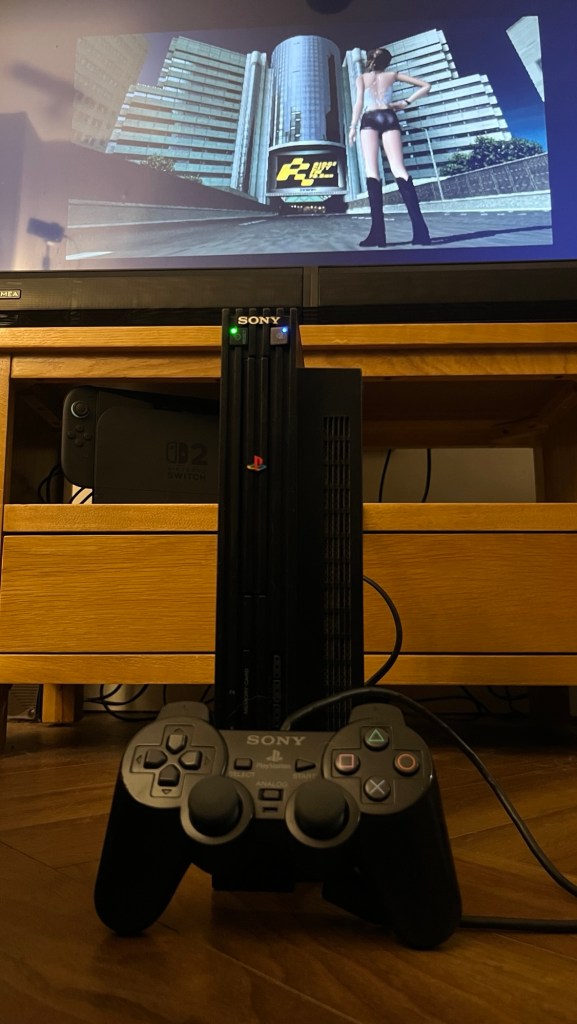

And because video game fandom is what it is and people get really bothered by negative opinions of games they’re sentimentally attached to: I should be clear that I do enjoy playing RRV. And the Gran Turismo games for that matter. They’re some of my favorites on the PS2, which is also thing I enjoy in case that wasn’t clear.

But also, who cares. If we can’t engage critically and earnestly with the things we find interesting, then what are we even doing here?

Thanks for reading!

@JetBrianRadio on BlueSky

GALLERY

R4 INTRO SEQUENCE: ALTERNATE CUT

I took a mental holiday to ridge city this year too. I replayed 4 and then decided to check out the psp games, 2 specifically, and it took me to Ridge City too. While also drinking craft beer in the Midlands/South Yorks as well! What a world!

Game has a lot of edges sanded off, to it’s detriment possibly, corners can sort of take themselves sometimes, and the rubber banding in the harder difficulties is just ridiculous, but it’s vibes are immaculate. Worth a punt if you haven’t tried. Inspired me to write about the location too.

https://backloggd.com/u/Grumpbags/review/2550112/

This is a great blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person